Sonic the Hedgehog CD/Development

From Sonic Retro

- Back to: Sonic the Hedgehog CD.

Sonic the Hedgehog CD went through many ideas and changes during the development process. What follows is a collection of items related to the game's development.

Contents

Development process

Although Yuji Naka and Hirokazu Yasuhara had gone to San Francisco to help mentor the newly-hired employees of the Sega Technical Institute and lead the development of Sonic the Hedgehog 2, Sonic creator Naoto Ohshima chose to stay behind in his native Japan, ready for his next assignment. Meanwhile, Sega of Japan, in preparation of the launch of their console add-on the Mega-CD, knew they wanted some sort of Sonic the Hedgehog title on the console to headline its existence, hoping its premier franchise would cause the new technology to be a success. At first, the company considered simply to develop an enhanced version of either the original Sonic the Hedgehog or of the upcoming Sonic 2, a practice that would shape much of the Mega-CD library in the years that followed. For one reason or another, however, it was decided that instead of porting an existing title, a new entry in the Sonic series would be developed from the ground up, which could take full advantage of the capabilities of the Mega-CD.

Once the decision was made, it didn't take long for Sega to involve Naoto Ohshima, making him the Director of the project and giving him free reign. Not wanting to make a game that was essentially the same as Sonic the Hedgehog 2, Ohshima contacted Yuji Naka and other members of the Sega Technical Institute during the initial planning stages, where both teams exchanged information about what the other wanted to do. It was during these early moments that Sonic CD started to take shape, Hiroyuki Kawaguchi becoming the art director and helping to shape the worlds of the game. Although comparisons can be made between the levels in the first Sonic the Hedgehog and its CD sequel, Kawaguchi made sure to make them visually stunning, standing out from anything that had yet been seen in the franchise.

Although the Sonic 2 team briefly considered the idea of time travel as a play mechanic, Ohshima fully embraced the concept, being in love with the idea of having the level Sonic was running in to suddenly change around him, the player instantly being warped to a different place. When time came to program the "Time Warp" sequences, however, the lead programmer Matsuhide Mizoguchi claimed that it was impossible to do such a thing on the hardware, and instead a "loading sequence" had to be created, the brief moment where Sonic can be seen flying through a green background with stars encircling him. Though Ohshima kept on pushing the programming team to find a way to circumvent this added screen (wanting the time travel to more resemble the instantaneous movement in Back to the Future), the programmers could not find a way to modify Naka's original code to create the desired effect. Years later, when Ohshima reflected back, he felt more than confident that if Naka had been the chief programmer on Sonic CD that he would have been able to find a solution, certain in his skills when it came to developing code.

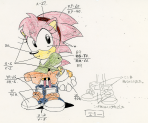

Another element that Ohshima wanted to include was the expansion of Sonic's cast of characters, wanting to provide not only a new protagonist but an enemy that could be marketed on the same level as Dr. Eggman. The game's visual designer, Kazuyuki Hoshino, was tasked with creating the designs of these two new characters for the game. The first of these, Amy Rose, was actually inspired by a character of the same name being used in the manga Sonic the Hedgehog. Wanting a twist on the standard kidnapping/romance scenario that had been overused in the gaming world, Amy was meant to be the one infatuated with Sonic, the blue hedgehog never showing any emotion back at her, his going to rescue her simply being another task to foil Eggman. The second new face in the game, Metal Sonic, was designed to be a sleek mechanical interpretation of the lead character, as opposed to the clunky Mecha Sonic that was drawn up for Sonic the Hedgehog 2. It may be because of this simple yet catching design, as well as his extensive use in advertising materials for the title, that has caused this version of a robot Sonic to outlast the others.

While never mentioned in any magazine (and wouldn't be discovered until the PC port in 1996) Sonic CD did have its own collection of missing elements, much as its co-existing Mega Drive sibling. Though levels like Hidden Palace, Dust Hill and Wood Zone became the stuff of legend due to their extensive game journalism coverage, little is known for certain about the unused and unfinished level to Sonic CD known to the Sonic-community as R2. The Taxman, developer of Sonic the Hedgehog CD (2011) claims concept art, shown in the Sonic CD developers diary, is in fact R2. He also confirmed the antlion enemy from the uncut extended ending video is from R2, likely meaning that the area it is found it is also R2. Some enemy sprites from R2 have been shared also. Before this was known there was quite a bit of speculation as to what the level could have been has arisen from various elements related to Sonic CD. The level was removed at some point before the earliest known prototype available, the 510 build.

Though a Sonic title, the team did not receive nearly as much pressure from Sega as the team responsible for Sonic the Hedgehog 2, as Ohshima would recount:

| “ | Sonic CD wasn't Sonic 2; it was really meant to be more of a CD version of the original Sonic. I can't help but wonder, therefore, if we had more fun making CD than they did making Sonic 2 [because we didn't have the pressure of making a "numbered sequel"]. | „ |

| — Naoto Ohshima, Director of Sonic the Hedgehog CD[1] | ||

Released in Japan on September 23rd, 1993, the game would go on to be considered not just one of the must have titles on the Mega-CD, but one of the best Sonic games ever produced, even though its existence did not cause the add-on to take off as Sega had hoped.

Westernization

Wanting just as much for the game to succeed as Sega of Japan, Sega of America prepped the Mega-CD (referred to as simply the "Sega CD" in the United States) for the release of Sonic's latest adventure. Though the code was already set to go on NTSC systems, the game was delayed for a month by executive decision. Looking over the game, SOA decided that they wanted to change the soundtrack already present within. The original tracks created for the Japanese release (which remained in the original European releases), they felt, were simply too similar to other electronic dance scores that were being produced at the time. Wanting to create its own identity, Sega contracted recently hired in-house musician Spencer Nilsen to rescore the entire game, giving him less than a month to do so.

Listening to the original soundtrack and appreciating what it did, he was also understanding of what SOA wanted to accomplish, immediately setting out to create an ambient sound completely separate from the original. Right off the bat, Nilsen contacted the female trio Pastiche, a pop/jazz group that performed in the area. Enlisting their help in creating the soundtrack, he took their ideas to heart, adding their vocal flairs to numerous tracks. Wanting a female influence in the soundtrack was a choice done specifically because of the introduction of Amy Rose in the game, wanting the female vocals to be an almost subliminal advertisement of her presence. The biggest contribution from the group was connected to the theme song, "Sonic Boom." The lead of the group, Sandy Cressman, was not only the singer to both versions of the theme, but was also responsible for the lyrics, coming up with the first few lines that she and the rest of her band helped finish.[2]

Released on November 19th, 1993, controversy over the soundtrack began almost immediately. Though a majority of the people who bought the game in the U.S. had no idea about the alternate soundtrack, those that did had an immediate backlash, the most prominent being in the pages of GameFan. Fully aware of the controversy surrounding his alternate soundtrack, Spencer Nilsen chose to remain calm about the outburst:

| “ | I think the controversy surrounding the two versions of the game soundtrack were really blown out of proportion. Honestly, I've had hundreds of people tell me that they LOVE the score I wrote for that game, and I'm sure the Japanese version has tons of fans as well, so everybody wins in the end… as it should be! After all… IT'S ONLY A GAME!!...I think critics were looking for reasons to bash the game, and so many critics are hardcore, loyal fans so they are not very objective. AND… they had all been playing the Japanese version for weeks or months before our version hit the streets, so it was like we replaced the music to Star Wars after the movie had been out for a while. From that perspective, I can't blame them. But to be honest, the game critics were always very kind to me and my collaborators, so a little bad press ain't the end of the world! | „ |

| — Spencer Nilsen, Sonic CD North American Special Edition Composer[3] | ||

In addition to the the music changes, another subtle, yet noticeable, change occurred within the pages of the manual. The new female character, Amy Rose, was renamed to Princess Sally, the name of the female character in the Sonic the Hedgehog animated series. In an attempt to market the two products together, SOA felt the best way would be to make players think the female characters were one and the same, even modifying the story inside to make Sonic and Sally already be on slightly romantic terms. Though early designs of the Sally character used in the television show featured a color scheme closer to Amy Rose (and was used for the first fifteen issues of the Archie comic book), most people were able to recognize the pink hedgehog sprite had nothing to do with the brown squirrel character in the show, Sonic's mannerisms in the game towards the girl being the opposite of someone in love. In the PC release, as well as every other game featuring her, the character has been referred to as Amy Rose, the name change being nothing more than a footnote in the history of Sonic's marketing in the west.

Sprites

Animation concept art

Unless otherwise noted, all of the artwork shown here is by Hisashi Eguchi, the chief key animator of Sonic CD's opening and ending animations. He was in charge of animating cuts 1-9 for the opening and cuts 11, 12 and 14 for the ending. He then corrected all of the drawings done by the other animators for the rest of the cuts.

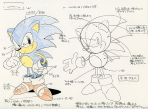

Character Model Sheets

Sonic in several different action poses and Sonic standing beside an Anton badnik which can be found in the stage Palmtree Panic.

A cleaner version of the first picture from Sonic Generations.

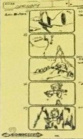

Storyboards

An early storyboard for the opening animation of Sonic CD.

Key animation

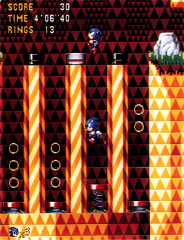

Sonic standing on an elevator in Wacky Workbench.

Sonic being attacked by a Mecha-Bu badnik and the elevator Sonic is standing on is being destroyed. This scene takes place in Wacky Workbench.

Sonic standing on top of two half destroyed Mecha-Bu badniks. This scene takes place in Wacky Workbench.

Sonic in an action pose as he jumps up after ripping off the buzz-saw from a half destroyed Mecha-Bu badnik. This scene takes place in Wacky Workbench Zone.

Animation cels

Opening

Ending

Character designs

Unless otherwise noted, the images below were drawn by Kazuyuki Hoshino, character designer for Sonic CD.

Sonic the Hedgehog in a dynamic pose, which would be transformed into a sprite used in the beginning of Wacky Workbench. Scan from Sonic Generations.

Line art of Sonic that would be used for the album Sonic the Hedgehog Remix. Scan from Sonic Generations.

A sketch of Amy Rose.

A finalized sketch of new antagonist Metal Sonic.

A character reference illustration of Metal Sonic featuring a front view, rear view, and side view profile.

An early concept sketch of Sonic and Metal Sonic for the Japanese Box Art cover, by Naoto Ohshima.

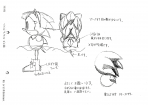

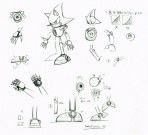

Concept art of Metal Sonic showing various angles and details of his design including a good look at different parts of his body and how they move and function.

Dr. Eggman from the front and back.

Enemy sketches

A collection of sketches of various enemies, including Tentou.

A detailed look at the sketch for Poh-Bee.

Boss concepts

Dr. Eggman sitting upon the VCCI-811 "President's Chair," unused in the final game. Of note is the "Eggman Industries" logo in the upper left, also unused. Scan from Sonic Generations.

One of Eggman's alternate methods of transportation, though this model is only seen in the D.A. Garden and the "Bad Ending" animation. Scan from Sonic Generations.

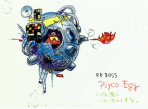

Initial concept art for the Eggman encounter in Metallic Madness, listed here as "Psycho Egg" from "R8." Scan from Sonic Generations.

Miscellaneous artwork

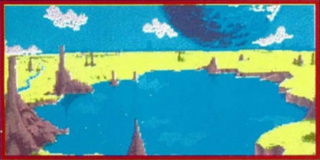

Artwork of Little Planet and Never Lake, used in the instruction manual for the Japanese version of the game.

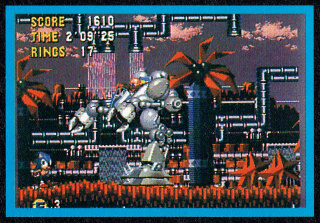

A document focusing on the Metal Sonic race in the final zone of Stardust Speedway.

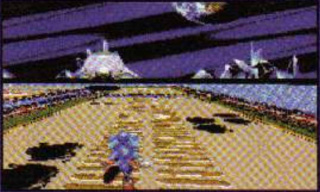

Sketches of how Sonic would look running in the psudo-3D Special Stages.

A collection of Little Planet flowers, both used and unused.

Concept art for the end-of-level Signpost.

Prototype screenshots

Yuusei Sega World

Sega released a handful of screenshots of Sonic CD during the Yuusei Sega World event. The game was playable on the show floor so it was also possible for publications to take their own screenshots, however the following is thought to have come directly from Sega.

All of these images are consistent with the 1992-12-04 prototype, which is believed to have been the version playable at the event.

Other screenshots

Opening animation

An early first look at one of the scenes shown in the opening animation to Sonic CD. There are slight minor differences between this screenshot and the final version. The chain that holds Little Planet to the Eggman rock is missing and the reflections of Little Planet and the chain in the water is also missing.

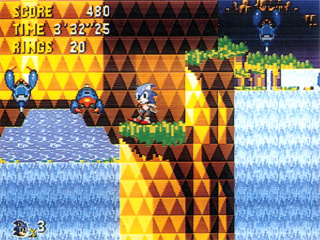

Palmtree Panic

Collision Chaos

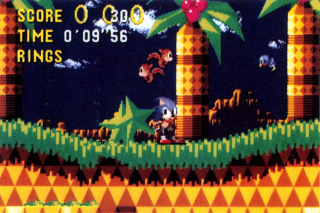

Curiously it was Collision Chaos that turned up in the gaming press first. Here we have an early version of the stage, including Anton and Mosqui enemies absent from this level in the final game.

Another screen of early Collision Chaos. The rotating platforms are circular shaped pegs instead of blue rectangle shapes as seen in the final and the background is less detailed and unfinished.[14][15]

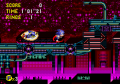

Collision Chaos' bad future with an entirely different colour palette. The clouds, giant mountainous shrubs, neon signs, and foreground objects opt for a more bluish colour scheme, while in the final game there are reds and washed-out greens. The pipes in the background are also red, while in the final version they're green.

Tidal Tempest

Special Stage

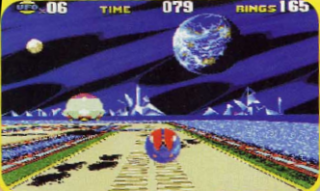

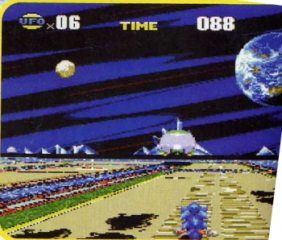

An extremely early screenshot of the Special Stage, featuring not only an unused background, but yellow balloons instead of UFOs.

Bonus Round

A single image of an unused Bonus Stage, it is unknown if it was an earlier version of the Special Stage, or if it was intended to be an extra round in addition to the Special Stage.

See also

- Sonic the Hedgehog CD prereleases - A collection of the ten known Sonic CD prototypes, and the differences between each.

External links

- Sonic CD - Developer Diary - Produced to help advertise the 2011 remake, Kazuyuki Hoshino talks about the development of the game, flipping through notebooks filled with concept art.

References

- ↑ Naoto Oshima interview by Gamasutra (December 4, 2009)

- ↑ Sandy Cressman interview by Sega-16 (September 9, 2005)

- ↑ Spencer Nilsen interview by Sega-16 (December_2008)

- ↑ [Sonic CD now out for everything except Nintendo consoles, post #1707 by The Taxman Sonic CD now out for everything except Nintendo consoles, post #1707 by The Taxman]

- ↑ File:DengekiMD JP 06.pdf, page 45

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 File:Famitsu JP 0212-0213.pdf, page 226

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 File:Famitsu JP 0212-0213.pdf, page 227

- ↑ File:DengekiMD JP 08.pdf, page 45

- ↑ File:DengekiMD JP 03.pdf, page 149

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 File:DengekiMD JP 03.pdf, page 45

- ↑ File:DengekiMD JP 07.pdf, page 45

- ↑ File:DengekiMD JP 05.pdf, page 45

- ↑ File:DengekiMD JP 04.pdf, page 45

- ↑ File:SegaForce UK 16.pdf, page 12

- ↑ File:GameFan US 0107.pdf, page 44

| Sonic the Hedgehog CD | |

|---|---|

|

Main page (2011) Manuals |

show;hide

Scrapped Enemies: Scrapped Bosses: Mega-CD: Windows PC:

Books:

Music: |